This article explaining the difference between soaps and detergents was originally published at Safe Household Cleaning.

The original source article is indented, and in green italics. I provide additional information and commentary [in brackets] and at the end.

What’s the difference between a soap and a detergent?

A decade or so ago, the difference between a soap and detergent was redundant when it came to a cleaning product. Virtually every product available was a detergent. However, in recent years, soaps are making a comeback.

The question is why?

To answer that question, we must first delve into the difference between a soap and a detergent.

The terms ‘detergent’ and ‘soap’ are often used interchangeably, and the two are similar – both act as surfactants, making dirt easier to disperse and wash away. Each has slightly different chemistry [1, 2, 4]:

-

- Soaps (e.g. sodium stearate) – fatty acids, normally derived from animal or plant sources. The ‘-carboxyl’ group of fatty acids can react with calcium or magnesium in hard water to form an unpleasant ‘soap scum’.

- Detergents (e.g. sodium lauryl sulfate [Note: SLS, has safety concerns] sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate [Note: more on this in my comments below]) – normally synthetic from propene, can have complex hydrocarbon structures (e.g. benzene rings). They are less likely to react with ions in hard water, and so do not form a ‘soap scum’. [Note: propene, AKA propylene, like most detergents, is produced from either petroleum, natural gas, or other petrochemicals.]

Generally, soaps are used in shampoos, body washes, and hand washes because there is a huge excess of water, so soap scum is just washed away. [Note: This is not actually true, as most shampoos and body washes are actually made of detergents, if you research the ingredients.]

However, commercial washing products (powders and liquids) were developed to use detergents to reduce soap scum. This scum can grey clothes and buildup in washing machines.

Unfortunately, the synthetic detergents came at their own cost. The synthetic detergents, certainly the earlier ones, had a tendency to cause contact dermatitis when they came into contact with sensitive skin. In addition, there have been many reported biodegradable and toxic concerns about a number of the synthetic detergents. What doesn’t help matters is many manufacturers are still not disclosing their cleaning product ingredients, so there are often trust issues with a product labeled with “anionic surfactants” as opposed to the actual ingredient [emphasis added].

So in recent years, we’ve seen a reemergence in soap based household cleaners. And there are ways to soften the water by adding ingredients such as ‘soda ash’ (sodium carbonate) to help soften water, reducing soap scum. [Note: there are several ways to formulate cleaning products to reduce soap scum, and adding carbonate is only one of them. Another approach is using fatty acids with shorter carbon chains. Soap scum can be greatly reduced if perhaps not completely eliminated.]

I like the sound of the natural approach – how are soaps made?

Humans have been making soaps using the same underlying technology for centuries. All soaps start from animal or plant fats (triglycerides), which are made up of fatty acids and glycerin. The choice of fat and its ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids will vary the texture of the resulting soap (e.g. mild, firm). Commonly used fats are listed below. [Nature’s Complement only uses plant sourced oils.]

| Animal Fats | Plant Fats | ||

| Raw Animal Fat | Resulting Fatty Acid | Raw Plant Fat | Resulting Fatty Acid |

| Tallow (beef fat) | Sodium tallowate* | Palm oil | Sodium palmate |

| Lard (pig fat) | Sodium lardate* | Palm kernel oil | Sodium palm kernelate |

| Laurel oil | Sodium laurate | ||

| Olive oil | Sodium oleate | ||

| Coconut oil | Sodium cocoate | ||

(The sodium salt can be changed to potassium by using potassium hydroxide, see below.)

The ‘soap’ or ‘surfactant’ action of soap is due to fatty acids. To liberate fatty acids, the raw triglycerides need to be heated with a strong alkali. Both sodium hydroxide (lye or caustic soda) and potassium hydroxide (potash) are commonly used as the strong alkali to make solid and liquid soaps respectively. The reaction forms fatty acid salts, which vary in texture depending on the alkali:

-

- Potassium fatty acid salts (e.g. potassium hydroxide + olive oil = potassium oleate) – these soaps are generally softer and can be liquids (e.g. hand soap).

- Sodium fatty acid salts (e.g. sodium hydroxide + coconut oil = sodium cocoate) – these soaps are generally harder (e.g. bar soaps).

(Both sodium and potassium hydroxide are harmful irritants (pH=13). Soap that is properly made uses less alkali than necessary, to ensure none remains in the final product. Finished soaps normally have a pH of 9-10, and contain no potassium or sodium hydroxide.)

So how are detergents manufactured?

Detergents are normally synthetic, manufactured from refining propene (a byproduct of crude oil). These were first produced due to a lack of animal and product fats during the World Wars. There are many types of detergent, and their surfactant action is more complex than soaps. Detergents can be categorized depending on the chemical mechanism in which they emulsify, with common examples including:

-

- Non-Ionic (e.g. alcohol ethoxylates)

- Anionic (e.g. sodium alkyl sulfate)

- Amphoteric (cocamidopropyl betaine)

Much like soaps, if detergents are properly produced they should not contain any remnants of the refining process. This can be more difficult to achieve and test for (not as simple as taking the pH), and so there is concern that many commercial washing detergents contain harmful and carcinogenic contaminants such as 1,4-dioxane and formaldehyde.

[Note: 1,4-dioxane is a well known carcinogen, and has been found as a residual contaminant in certain types of detergents and nonionic surfactants in numerous peer reviewed scientific studies. In the studies linked above, 78% of detergents tested and 30% of nonionic surfactants tested were contaminated with 1,4-dioxane.This is due to the fact that 1,4-dioxane is a byproduct of a chemistry process known as “ethoxylation” which is used to make several types of detergents. So it is not uncommon at all for detergents to cause human exposure to this carcinogen.]

[Note: Similarly, formaldehyde can also be found in detergents, and in addition to being a carcinogen, it can also cause contact dermatitis.]

I’d like to buy a soap based cleaner – how do I spot it on the label?

Quite often you’ll see a reference to Sodium Hydroxide or Lye and an oil or fat. If you see those listed, it’s a good chance you’re looking at a soap based cleanser.

An alternative, particularly in liquid cleansers, is to look for Potassium Hydroxide with an oil or a fat.

Alternatively, manufacturers will label the actual resulting saponified oil in their ingredients, and the name of this depends on the oil actually used.

For example:

-

- Sodium palmitate (Lye and Palmitic Acid)

- Sodium stearate (Lye and Stearic Acid)

- Sodium oleate (Lye and Oleic Acid)*

- Sodium cocoate (Lye and coconut oil)

- Sodium palmate (Lye and palm oil)

- Potassium palmitate (Potassium Hydroxide and Palmitic Acid)

- Potassium stearate (Potassium Hydroxide and Stearic Acid)

- Potassium oleate (Potassium Hydroxide and Oleic Acid)*

- Potassium cocoate (Potassium Hydroxide and coconut oil)

- Potassium palmate (Potassium Hydroxide and palm oil)

Note, Sodium Oleate can originate from oleic acid found in lard or olive oil. The only way to differentiate from these products is to look for soaps listed as ‘vegan’ or ‘animal product-free’. An alternative is soaps that use responsibly sourced plant-based ingredients, like sodium cocoate sodium palmate.

Another common means of labeling soaps is to just refer to Saponified Oil. Unfortunately, there’s no way of telling what kind of oil was used. For cleaning purposes, it shouldn’t matter too much. However, for vegetarians or vegans, you’ll need to look for the vegan label to be sure.

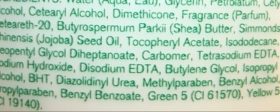

How are detergents labeled?

Detergent ingredient labels are generally easier to understand but lack the detail of soap washing products. As with the formulations listed above, washing detergents will normally only list ‘anionic surfactants’ or ‘nonionic surfactants’. Some manufacturers provide more specific information on their website, but there is no other way to determine the composition – particularly frustrating for those with allergies to some detergents. Hence the recent trend in soap-based cleansers.

So what is better, a soap or detergent?

This really depends on personal preference. [Note: preference regarding whether you care about your health of not.] I have really sensitive skin, so tend to buy soap based cleaners. However, what’s most important to me is the manufacturer discloses the ingredients, and I can make a judgment from there. There are some amazing detergent based cleansers out there. And, there are a number of products that contain both soap and detergent. As long as the product discloses the ingredients and I’m not irritated by the ingredients, I’ll often buy it.

But that’s only my opinion. How do you choose yours?

References

[1] Smulders, E., von Rybinski, W., Sung, E., Rähse, W., Steber, J., Wiebel, F., & Nordskog, A. (2007). Laundry detergents. Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA

[2] Bajpai, D. (2007). Laundry detergents: an overview. Journal of OLEO Science, 56(7), 327-340.

[3] Unilever. (2018). Persil Products. www.persil.com [Accessed: 6/2/18]

[4] American Cleaning Institute. (1994), Soaps and Detergents. www.cleaninginstitute.org [Accessed: 6/2/18]

Additional Information And Commentary

It is a truism that the most effective lies have an element of truth to them. After all, something that is obviously completely false is easy to disprove. However when there is a small kernel of truth, it is much easier to use that to create confusion and FUD (Fear Uncertainty and Doubt), to conjure untruths from truth. Such is the case with detergents versus real soap.

While some of the critiques of real soap versus detergent are true (i.e. soap scum), they are greatly overblown and also vary depending on how the overall product is formulated. If the formulator is smart, s/he can greatly reduce the production of soap scum from the end product.

On the other hand, the point that is always missed or intentionally ignored by proponents of detergents is the consideration of human toxicology and safety. Has your detergent been tested for safety in toxicology experiments? Some have, but most have not. But they should be, given that some of the detergents that have been tested have shown health and safety concerns, particularly the ones contaminated with 1,4-dioxane, formaldehyde, and other petrochemistry byproducts. Alcohol ethoxylates are likely commonly contaminated with 1,4-dioxane. Cocamidopropyl betaine or contaminants from manufacturing is/are common cause of contact dermatitis. Finally, it’s worth pointing out that the most common class of detergent surfactants is Alkylbenzene sulfonates. These were mentioned in the article above as “dodecylbenzenesulfonate”. Alkylbenzene sulfonates are made using benzene, which is a known carcinogen. While I have not (yet) found any evidence that any residual benzene remains in the Alkylbenzene sulfonate end products, in looking at the chemistry synthesis it strikes me that it could be possible if a manufacturer was not careful.

So the mainstream debate of detergent vs. soap more often than not focuses only on the chemistry and functionality. But we need to do a better job of evaluating safety and health impact before we can make a fully informed and valid comparison of all the pros and cons.

For Health,

Rob

Nature's Complement is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. If you purchase products on Amazon through any of our affiliate links, we get a small percentage of the transaction, at no extra cost to you. We spend a lot of time writing the articles on this site, and all this information is provided free of charge. When you use our affiliate links, you support the writing you enjoy without necessarily buying our products. (However we would appreciate if you would do that too!) Thank you for helping to support our work, however you choose to do so.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information and/or products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.